“Extra-Special Illegal”

How Canada's Femicide Law Challenges Equal Justice

I can’t remember when I first heard about hate-crime laws, but I’ve always thought they were stupid.

It turns out I was wrong.

Not completely, but at least where the US is concerned there is an historical justification for them.

However, before we get into the history of them, let’s ensure we all understand what we’re talking about. A hate-crime is defined not just by the harm done, but by why the harm was done:

Targeting based on race, religion, ethnicity, sexuality, disability, etc.

Intended to intimidate or subordinate an entire group

They are seen as an attack on social equality itself

With the exception of the third bullet the logical amongst us might be inclined to think, “yes, this bad, but aren’t murder, assault, and threats already illegal? What does adding a new law do?”

A little American History

After the US Civil War, Southern states routinely:

Refused to prosecute crimes committed against Black Americans

Underenforced the law when the perpetrator was white

Used all-white juries to acquit even in open, notorious violence

This wasn’t a failure of capacity; it was intentional non-enforcement. State sovereignty was being used to nullify constitutional rights.

During Reconstruction the federal government introduced the first “hate-crime” laws, although they did not use the term. The Enforcement Acts/Ku Klux Klan Acts (1870–1871) made it a federal crime to:

Conspire to deprive someone of civil rights

Use violence or intimidation to prevent equal protection under the law

The trigger for federal jurisdiction was state failure or refusal to protect. The logic being that if a state would not punish racially motivated violence, the federal government must step in. This logic became the basis for future hate-crime laws.

Motivation mattered because it prevented the federal government from stepping if it simply disagreed with a state court ruling. The federal government had to show:

The crime was not just interpersonal

It was meant to enforce racial hierarchy

It undermined constitutional guarantees

This same logic came into play during the Civil rights era revival (1950s–1960s) when similar patterns emerged:

Local police fail to protect civil rights workers

Prosecutors decline to charge white perpetrators

Juries acquit despite strong evidence

Congress responds with:

Civil Rights Acts

Expanded federal jurisdiction over bias-motivated violence

Again, the driving concern was state abdication, not symbolic punishment.

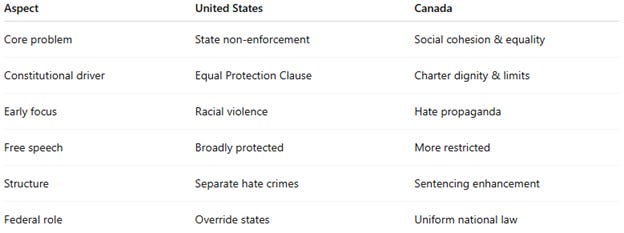

Canada is different

Unlike the US, Canada has had a single national Criminal Code since 1892:

Provinces do not define crimes

There was no equivalent of U.S. states refusing to prosecute murders

No constitutional need for “federal override” of local criminal law

So Canadian hate-crime law did not arise to fix non-enforcement, they are meant to address social cohesion, minority protection, and symbolic harm.

Canada’s history is not without group-targeted violence and discrimination:

Anti-Indigenous violence and coercion

Anti-Catholic and anti-Irish riots (19th century)

Anti-Asian violence (e.g., Vancouver riots, Chinese exclusion)

Antisemitism (e.g., Christie Pits riot, “None is too many” refugee policy)

However, if the concern is that the federal government was refusing to prosecute crimes against minorities, adding a new federal law would not solve this problem.

Canada’s approach to hate-crimes did not arise to fix non-enforcement, it arose to address social cohesion, minority protection, and symbolic harm and grew out of the post-Holocaust legal thinking. Its key influences were: